![aitzchayyim_0]() It's been about two months since I posted a piece of my writing on this blog. I was deeply immersed in supporting my sister Inbal on her final journey, which ended with her death on September 6, 2014.

It's been about two months since I posted a piece of my writing on this blog. I was deeply immersed in supporting my sister Inbal on her final journey, which ended with her death on September 6, 2014.

One day I will find the words to write about Inbal here. (You can read her obituary here.) Over the last seven years I've on occasion mentioned Inbal and her ongoing challenge of living with cancer. I don't recall writing in any significant way about what it has been like to accompany her way of facing cancer. I kept it mostly separate, except when it seemed almost inhuman not to mention it. Now, having accompanied her, being so profoundly involved, and learning as much as I have, I anticipate continuing to learn. This is a way to reweave my personal experiences and my work in the world.

The period of sitting Shiva, the Jewish custom of gathering community for seven days after someone dies, is over. I am now ready to slowly emerge into the next phase of my life, and writing about this period is a small step in that direction.

Trusting life

None of what I learned about myself and about life through this very demanding experience is new in its entirety; it is a deepening, at times surprising, of what I have known or intuited before; and it is an entirely new territory. I realized at one point that as little as we get prepared for parenting (ultimately everyone has to learn it newly, with their own children), there is even less to prepare us for being with a loved one as they are dying. Moreover, this is a topic rarely talked about, whereas parenting is. Most of us don't know what to say to each other about death, whereas so many easily share their opinions and experiences of parenting, and there are books, norms, and wisdom commonly available.![More...]()

I never would have guessed that the most important change I would be called to make would be increasing my trust - in myself and in life. As a result, emerging from this experience, with all the immense sorrow and loss, I see that I have become bigger and stronger. Gradually over time, I let go of more and more of my usual activities as the mobilization to support Inbal intensified. There was no question of what was "right"; only a kind of knowing what I had energy for, and I never forced myself to do anything. I rarely do anyway, and, still, I now have even more appreciation for what a fine-tuned instrument listening to myself can be.

Part of trusting included overcoming the subtle ways in which I have tended to defer, even to lose track of what's important to me, in the face of any apparent challenge. My commitment to Inbal was so strong, and the knowledge about what I could offer her so clear, that I found strength to say and do things with much less concern about how others would respond. This went as far as finding a new role within my family of origin, and supporting all of us, including my mother, to get closer to each other as we had our last meaningful conversation with Inbal before my mother headed back home to Israel, where she and Arnina live.

![bnaimitzvahbanner]() I am still deeply digesting what this means for what comes next in my life: what would it take for me to continue this trust, this willingness to persist in pursuing what feels deeply true, when it comes to what matters to me? Why was I able to do this when it involved supporting someone dear to me, and much less so - at least so far - when it is about supporting myself?

I am still deeply digesting what this means for what comes next in my life: what would it take for me to continue this trust, this willingness to persist in pursuing what feels deeply true, when it comes to what matters to me? Why was I able to do this when it involved supporting someone dear to me, and much less so - at least so far - when it is about supporting myself?

A new revelation about trusting life arose in learning even more specifically about how much death is part of life. This lesson came to me from two sentences that Inbal said. One was her overall experience of, in her words, "dying fully in touch with loving life, and yet, also, fully accepting death." The paradox contained within this frame continues to move me, both as the person who lost my beloved, and as a human being learning about life. Acceptance, as I have come to understand about other things, doesn't at all mean liking what is happening; it only means letting go of any residual inner fighting against what cannot be prevented. Beholding so closely someone who has attained that degree of inner peace is a grace beyond words. Then, in the last few days Inbal also said: "My body needs to die." This was altogether new to me, the idea that death emerges from life, and that, being deeply attuned to life, we might be able to discern to such a degree what life is leading us to.

Appreciating Judaism

I have some deep qualms about the tradition I am part of. Some of the core foundations of the practice, including the perspective on women, the degree of fear of non-Jews, and the overall approach to life based on fear and punishment, unsettle me sufficiently that, for the most part, I have distanced myself from any of the practices. Here, too, I experience paradox, because despite all the ambivalence, I also hold a deep respect for a people that has found a way to remain alive, vibrant, and regenerative for two thousand years in exile, and for the deep wisdom about human life, and love of the human spirit, that infuse the texts, the customs, and the stories.

When it comes to death, as I acquainted myself with more of the tradition, I became more and more astounded by that level of wisdom. In fact, one of Inbal's non-Jewish friends who was with us in the circle that held her for the last few days, told us that she was planning to ask to apply Jewish customs to her own death. Given that I imagine many of you who read my blog are not Jewish, and even those who are may not be familiar with the customs, I want to share a bit more.

Jewish customs about death are based on two core principles: honoring the dead and comforting the mourners. Until the burial is complete, the entire focus is on the former, to the point where, according to tradition, condolences are not given until after the funeral. The whole point is to maintain the dignity of the person who died. This is why Jews have always aimed for burying their dead within 24 hours, before the body loses its connection with the person and becomes a "thing" and fast enough that the mourners can take the necessary actions and move quickly enough to focus on their grief. Within this time, the body is never left alone. The hours after the death when Inbal's body was in the house and we took turns, through the night, watching it, were unexpectedly meaningful, an opportunity to be in silence and cherish the mystery and the being we all loved so much.

A careful ceremony of washing the body and dressing it for the funeral follows, and I had the honor of participating in this process. Traditionally, Jews have not used coffins, and have opted, instead, to bury their dead only wrapped in cloth. Only few places allow people to be buried like that, and Inbal was buried in one of those places, Fernwood Cemetery in Marin County. There is nothing like shoveling hand-dug soil on the body of a loved one after it's put in the grave to drive home the finality of the loss.

As soon as the body is covered and the family goes home, the focus shifts to the mourners. Judaism is a community-based way of life, far beyond a religion per se. My ancestors recognized that in the face of tremendous loss, the community must gather and support the mourners. According to Jewish law, mourners are strictly forbidden from cooking and must be fed, for an entire week, by their guests.

And so began the Shiva (seven in Hebrew), a week of people coming with food, love, and memories. No two days were alike. Some of the gatherings at Inbal and her wife Kathy's home drew over 40 people, and some of the time at my place only one person was visiting. Even people I had been estranged from for years showed up to offer their presence, to reconcile, to honor Inbal. For an entire week I was held by a wide circle of people, including some of my closest friends who came from afar to make sure I didn't go through the first few days alone. My remaining sister, Arnina, was here for most of that week before finally heading back to Israel after being here for the last month of Inbal's life, keeping me the best company I can imagine as we both came to grips with the new reality.

The Jewish tradition creates landmarks in the inevitable process of coming back to life, ensuring that people are surrounded by community for the most disorienting days, during which the task is to support the mourners in focusing as inward as possible, as deeply as possible. Then, for the rest of the first month, a less intense focus, and, again, for the rest of the first year. We all know that mourning never ends fully, and yet, sooner or later, we heed the insistent call of life, and allow the loss to become part of the fertilizer of the rest of our lives.

Empty space

![sfjcctorah]() For some years now, I've had an item on my growing to do list: I wanted to find a way to be together with other Jews in some way that honored what I love about Judaism without the trappings of the rituals. Like most non-urgent items on that list, there was no space to attend to this desire, as most of my non-work energy was entirely devoted to caring for Inbal. As plans for the Shiva became clear, I knew I wanted to do something that would connect with other people for whom Nonviolent Communication (NVC) and Judaism were both meaningful. I asked the rabbi who performed the funeral, a long-time friend, for some text I could use to bring together the two, and she offered me a Hassidic text that immediately resonated. It was all about empty space.

For some years now, I've had an item on my growing to do list: I wanted to find a way to be together with other Jews in some way that honored what I love about Judaism without the trappings of the rituals. Like most non-urgent items on that list, there was no space to attend to this desire, as most of my non-work energy was entirely devoted to caring for Inbal. As plans for the Shiva became clear, I knew I wanted to do something that would connect with other people for whom Nonviolent Communication (NVC) and Judaism were both meaningful. I asked the rabbi who performed the funeral, a long-time friend, for some text I could use to bring together the two, and she offered me a Hassidic text that immediately resonated. It was all about empty space.

Empty space, first, which God had to make by withdrawing himself in order to create the world. How God can both exist and not exist in that space is, as the text tells us, a matter we will only understand in the future. Paradox, once more, that creative, generative tension that forces something new to emerge. Empty space, the text goes on, that exists in the disagreements between the sages and allows for new understanding. That was the connection with NVC: dialogue, true and deep respect for different perspectives, a listening and an understanding that allows for learning. Dialogue and the creation of the world as parallels.

The small, motley crowd of people that gathered - some for community, some for the purpose I had intended, and some for various other reasons, ranging anywhere from fellow Israelis to non-Jews - came together in appreciation of the brilliance and beauty of the text. We found connections and meaning - with NVC, with Inbal's death, and with our own experiences of love and death. More than anything, we were all somehow taken by the idea that disagreement had such potential for creative outcomes.

Then, finally, the empty space in my life left by Inbal's departure. I didn't instantly see the connection, not until two people, on that same day, sent me emails literally mentioning empty space, as if to make the point inescapably clear. Empty space because all the energy and presence I brought to caring for Inbal is gone. Empty space because the irreplaceable anchoring in life that Inbal gave me by her pure, simple, and easy love of me is now a gaping hole. Empty space because the one and only person who accompanied me on a daily basis is no longer able to do it. Empty space because the person I would turn to, even close to her death, for solace, for advice, for a place to just be me, for perspective, for glow, is gone forever. Empty space because my colleague and co-creator will never come back to that role, something I was still hoping for after years of struggle with cancer. Empty space because I lost the person most like me in the whole world. No wonder the world feels so different.

Empty space, as uncomfortable and impossible to understand as it is, is the ground of newness. I want to tend to that empty space with utmost mindfulness, to bring to it all I know, all I have learned, all I have experienced, all of my capacity for intention and choice, never to put anything into it that is not by choice, that is habitual or unconscious. Only what I truly want, what is aligned deeply with my mission and values, or what would be just simple delight or pleasure in life. Only what would honor the gifts she has given me in her unbearably short life. I asked Inbal, shortly before she died, for any guidance to my life. She smiled and said, simply: "I want all the best for you; I want you to do truly what you want."

Community

That first week, as is often with death and loss, created an openness in the air that was making everyone be closer to how I want to be all the time: deeply authentic, vulnerable, willing to risk, and full of intention. My heart aches for that quality abundantly in everyday life, for people who share my passion and willingness to aim to live this way every second of our waking life.

Before the Shiva started, I had a dread that Arnina and I would be sitting alone and that no one would come. That did not materialize. There was a steady trickle of people who came, there were sweet surprises, there were memories of Inbal that touched me, deep conversations about community, and a constant presence of people with me for days, even after Arnina left.

I am blessed with a really large network of people who love me and whom I love. These days since Inbal died really crystallized for me the difference between that network and what I call community. For one thing, community means the relationships are between everyone and everyone else, not just each person and me. For another, community means doing various things together, not just loving each other. There is no structure to my life. The only community I knew in the last while was Inbal and her family, and the people who came together around Inbal, both in support of her and in celebration of the vibrancy she inspired all around her to live.

At one point I invited those present in my house to engage in a conversation about community: do they have it? Do they want it? How do they navigate the gap between our human need and evolutionary legacy of living in community, and the harsh alienation and isolation of modern life that makes community almost impossible? What emerged was a tiny bit of solace from the shared fate: none of us had good answers.

My organism knows this is not enough. I am constitutionally incapable of masking the need for community, and I want to create it. Yet this is no time for investing energy. This, mourning and loss, is a time for harvesting, not for sowing.

A friend wrote to me and said: "The presence of people during the Shiva is very holding and healing! After the Shiva, when the hold gets looser, you can feel the presence of the absence more sharply."There is no end to this piece, because the mourning will likely take the rest of my life. It feels important to share, though, even when the loss is so fresh, because the loss of community in all of our lives since the onset of modernity is so intense and so forgotten at the same time. In times like this, there is no way to mask that loss. I have every intention of doing something, at least for myself, to create community, locally, once I get through this initial period and regain some resilience and energy. For now, I will lean on the many people I know and love, as individuals absent community, to create a bridge between the loss and the future life I might have.

The three artworks on this page are by Nancy Katz, from an online exhibition of her work on the Tikkun art gallery.

2. Be Emotionally Expressive. We live in an age of data overload. To stand out from everything else that can grab the audience's attention, you need to be present. You need to feel the emotions that match what you are talking about. Which would you prefer - (1) a speech with no flubs, proper elocution, and perfectly timed pauses or (2) a speech with a few mistakes that the speaker acknowledged and self-deprecatingly laughed at along with a few moments where the speaker lost track after being overwhelmed by the intensity of reliving shared memories? If you find it difficult to express your emotions openly in front of a room full of people, your body can help. Use exaggerated facial expressions, move your entire body closer or farther from the crowd, crouch down or stand up taller, do what is needed for you to feel and for the audience to feel what you are feeling.

2. Be Emotionally Expressive. We live in an age of data overload. To stand out from everything else that can grab the audience's attention, you need to be present. You need to feel the emotions that match what you are talking about. Which would you prefer - (1) a speech with no flubs, proper elocution, and perfectly timed pauses or (2) a speech with a few mistakes that the speaker acknowledged and self-deprecatingly laughed at along with a few moments where the speaker lost track after being overwhelmed by the intensity of reliving shared memories? If you find it difficult to express your emotions openly in front of a room full of people, your body can help. Use exaggerated facial expressions, move your entire body closer or farther from the crowd, crouch down or stand up taller, do what is needed for you to feel and for the audience to feel what you are feeling.

While I’m surrounded and hounded by the Imperious Trio, an ER nursing aide helps my mother get dressed. The Trio finally departs; I’m a puddle of goo. This aide-- a far kinder and gentler caregiver-- figuratively scoops me up and asks if I need anything before we go.

While I’m surrounded and hounded by the Imperious Trio, an ER nursing aide helps my mother get dressed. The Trio finally departs; I’m a puddle of goo. This aide-- a far kinder and gentler caregiver-- figuratively scoops me up and asks if I need anything before we go. The aide also thinks to fetch one of the paramedics who brought my mother in, so I’ll know where to find her getaway car. The paramedic is also friendly and helpful. He calls up a map on a computer for me to study, as I am unfamiliar with the area. He points out the Jeep’s location and understands my intense curiosity about my mother’s route. When I see where the Jeep is, I know instantly how she got there. Five miles from home, she’d turned onto a busy road that, 50 miles later, dead-ended at a security checkpoint at a Satellite Development Facility. That chance destination is what returned her to us so quickly. The paramedic shares my delight at solving this mystery and marvels with me at our good fortune.

The aide also thinks to fetch one of the paramedics who brought my mother in, so I’ll know where to find her getaway car. The paramedic is also friendly and helpful. He calls up a map on a computer for me to study, as I am unfamiliar with the area. He points out the Jeep’s location and understands my intense curiosity about my mother’s route. When I see where the Jeep is, I know instantly how she got there. Five miles from home, she’d turned onto a busy road that, 50 miles later, dead-ended at a security checkpoint at a Satellite Development Facility. That chance destination is what returned her to us so quickly. The paramedic shares my delight at solving this mystery and marvels with me at our good fortune. In recent decades, hospitals and health care practitioners have become increasingly

In recent decades, hospitals and health care practitioners have become increasingly  It was as if I’d stepped back in time, when it was standard for hospitals to harbor a culture of looking down one’s nose at the patients and families. Copping this attitude is all too easy, especially in understaffed ERs and intensive care units, wherein stressed caregivers may look at patients who are in poor condition, perhaps struggling to be coherent, attentive, or sensible, and see them as incompetent, difficult, even crazy. Patients, as well as their family members, are also likely to be overwhelmed with painful emotions such as anxiety, sadness, and anger, and as a result, they can be challenging to interact with. But when caregivers can view these agitated states as natural responses to the duress of hospitalization (and perhaps what preceded it), it can help them remember that these folks aren’t trying to be difficult or delusional. Being mindful that patients and families are experiencing trauma and struggling to cope, it’s far easier to provide care with compassion.

It was as if I’d stepped back in time, when it was standard for hospitals to harbor a culture of looking down one’s nose at the patients and families. Copping this attitude is all too easy, especially in understaffed ERs and intensive care units, wherein stressed caregivers may look at patients who are in poor condition, perhaps struggling to be coherent, attentive, or sensible, and see them as incompetent, difficult, even crazy. Patients, as well as their family members, are also likely to be overwhelmed with painful emotions such as anxiety, sadness, and anger, and as a result, they can be challenging to interact with. But when caregivers can view these agitated states as natural responses to the duress of hospitalization (and perhaps what preceded it), it can help them remember that these folks aren’t trying to be difficult or delusional. Being mindful that patients and families are experiencing trauma and struggling to cope, it’s far easier to provide care with compassion. Seeing patients and families as incompetent is another trap. Indeed, they often do appear dazed and confused. But again, it helps to remember that dazed and confused are natural responses to the shock of hospitalization and the unfamiliar world of medical terminology, conditions, treatments, and equipment. It is normal for patients and families to need information repeated, plus plenty of time to form coherent questions. Rather than judgment and lecturing, they need caregivers to be collaborative partners as they learn to navigate the new terrain. Being met with bossiness only exacerbates distress, as what happened to me. Is it any wonder I played the PhD card? I was struggling to prove that I was competent. I wanted to assert that I’d been doing a stellar job of care coordination for the past five years, and even with this new monkey wrench in the works, our team would be back on track by nightfall.

Seeing patients and families as incompetent is another trap. Indeed, they often do appear dazed and confused. But again, it helps to remember that dazed and confused are natural responses to the shock of hospitalization and the unfamiliar world of medical terminology, conditions, treatments, and equipment. It is normal for patients and families to need information repeated, plus plenty of time to form coherent questions. Rather than judgment and lecturing, they need caregivers to be collaborative partners as they learn to navigate the new terrain. Being met with bossiness only exacerbates distress, as what happened to me. Is it any wonder I played the PhD card? I was struggling to prove that I was competent. I wanted to assert that I’d been doing a stellar job of care coordination for the past five years, and even with this new monkey wrench in the works, our team would be back on track by nightfall. I turn my back and wander 20 feet away to phone my sister and cement our plan for her to pick up the Monday Caregiver and meet me at the satellite facility. I give her the easy directions: “Just go to the end of the road! Hahahaha!”! I walk back to the car as I seal the deal, when I notice to my horror that it’s empty. My mother is not in the passenger seat. She is not in the back seat. She isn’t standing outside the car. She is not in the parking lot!

I turn my back and wander 20 feet away to phone my sister and cement our plan for her to pick up the Monday Caregiver and meet me at the satellite facility. I give her the easy directions: “Just go to the end of the road! Hahahaha!”! I walk back to the car as I seal the deal, when I notice to my horror that it’s empty. My mother is not in the passenger seat. She is not in the back seat. She isn’t standing outside the car. She is not in the parking lot! Okay, think like a demented person! The parking lot isn’t that big. My car is the sixth one in from the circular drive, 75 feet from the ER entrance. As I make my way to the gigantic doors, I frantically peer around the other cars and cast my glance far and wide. There are paths between other buildings. A glade of fir trees. Traffic speeds by on Broadway.

Okay, think like a demented person! The parking lot isn’t that big. My car is the sixth one in from the circular drive, 75 feet from the ER entrance. As I make my way to the gigantic doors, I frantically peer around the other cars and cast my glance far and wide. There are paths between other buildings. A glade of fir trees. Traffic speeds by on Broadway. Adrenaline coursing through my veins for a second time today, I take her by the hand, while sharing the glad tidings with my sister. As we exit, I wave and call out to anyone who might understand the implications of what just happened, “Okay, I get it! She wanders. I’m ramping up care. I’m figuring this out!”

Adrenaline coursing through my veins for a second time today, I take her by the hand, while sharing the glad tidings with my sister. As we exit, I wave and call out to anyone who might understand the implications of what just happened, “Okay, I get it! She wanders. I’m ramping up care. I’m figuring this out!” Caio! Phil Zimbardo here. I’d like to share some information we’ve gathered about how men’s time perspectives affect their views on sex and loving relationships with partners. Here goes:

Caio! Phil Zimbardo here. I’d like to share some information we’ve gathered about how men’s time perspectives affect their views on sex and loving relationships with partners. Here goes: Being stuck in any one of these categories suggests an extreme personality type, which is why it’s easy to find stereotypical examples for each. But most people are a combination of perspectives. Whether you are wondering which time perspective you are or if you've already figured it out, you probably want to know what an ideal Sex Time Perspective is. Assuming you want to have or eventually have a long-term romantic and fulfilling social-emotional-sexual relationship, it would be a blend of moderate Future Oriented and Present Hedonist, with a dash of Past Positive. If you strongly resonated with the Past Negative or Present Fatalist perspectives, you may want to analyze the depressing impact it’s had on your love life, how you can remove those negative perspectives’ limits, and consider how to better filter those potential partners. It is important, guys, for you to also understand your partner's dominant time zone since their positive compatiability with yours is one key to happiness.

Being stuck in any one of these categories suggests an extreme personality type, which is why it’s easy to find stereotypical examples for each. But most people are a combination of perspectives. Whether you are wondering which time perspective you are or if you've already figured it out, you probably want to know what an ideal Sex Time Perspective is. Assuming you want to have or eventually have a long-term romantic and fulfilling social-emotional-sexual relationship, it would be a blend of moderate Future Oriented and Present Hedonist, with a dash of Past Positive. If you strongly resonated with the Past Negative or Present Fatalist perspectives, you may want to analyze the depressing impact it’s had on your love life, how you can remove those negative perspectives’ limits, and consider how to better filter those potential partners. It is important, guys, for you to also understand your partner's dominant time zone since their positive compatiability with yours is one key to happiness.  To conclude: I have so far been speaking only of wars between nations; what are known as international conflicts. But I am well aware that the aggressive instinct operates under other forms and in other circumstances. (I am thinking of civil wars, for instance, due in earlier days to religious zeal, but nowadays to social factors; or, again, the persecution of racial minorities.) But my insistence on what is the most typical, most cruel and extravagant form of conflict between man and man was deliberate, for here we have the best occasion of discovering ways and means to render all armed conflicts impossible. I know that in your writings we may find answers, explicit or implied, to all the issues of this urgent and absorbing problem. But it would be of the greatest service to us all were you to present the problem of world peace in the light of your most recent discoveries, for such a presentation well might blaze the trail for new and fruitful modes of action—Albert Einstein, in his famous 1931 letter to Sigmund Freud

To conclude: I have so far been speaking only of wars between nations; what are known as international conflicts. But I am well aware that the aggressive instinct operates under other forms and in other circumstances. (I am thinking of civil wars, for instance, due in earlier days to religious zeal, but nowadays to social factors; or, again, the persecution of racial minorities.) But my insistence on what is the most typical, most cruel and extravagant form of conflict between man and man was deliberate, for here we have the best occasion of discovering ways and means to render all armed conflicts impossible. I know that in your writings we may find answers, explicit or implied, to all the issues of this urgent and absorbing problem. But it would be of the greatest service to us all were you to present the problem of world peace in the light of your most recent discoveries, for such a presentation well might blaze the trail for new and fruitful modes of action—Albert Einstein, in his famous 1931 letter to Sigmund Freud To lose weight or change the way you eat, you need to get and stay motivated. You have eating habits that are strongly ingrained: You’re accustomed to eating a certain amount ad certain types of foods at certain times. If you need to lose a substantial amount of weight, you may be talking about changing lifelong habits—habits you’ve probably had even longer than you’ve carried those excess pounds.

To lose weight or change the way you eat, you need to get and stay motivated. You have eating habits that are strongly ingrained: You’re accustomed to eating a certain amount ad certain types of foods at certain times. If you need to lose a substantial amount of weight, you may be talking about changing lifelong habits—habits you’ve probably had even longer than you’ve carried those excess pounds. As stated in my

As stated in my  phenomenon of what we clinicians call "religious preoccupation" is striking: Psychotic patients regularly report hearing the voice of God or

phenomenon of what we clinicians call "religious preoccupation" is striking: Psychotic patients regularly report hearing the voice of God or

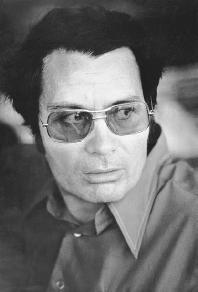

Messianic religious sects like Al-Qaeda and ISIS are not unlike the psychedelic cult or "Family" that unquestioningly served and worshipped Charles Manson, obediently butchering the pregnant Sharon Tate and eight others at his bidding in the summer of 1969. Manson was convinced that by instigating a race war in America as a result of the random killings, he and his group would seize power in the ensuing pandemonium of "Helter Skelter." This was his own messianic delusion of being a savior, of saving the world. From what I've seen in taped interviews over the years, Manson appears to be at once narcissistically grandiose, intermittently psychotic, paranoid, and profoundly antisocial. He bitterly alleges--with some merit, given his horrific background before the Hollywood massacre-- that the world has done him wrong, which gives him the right to do the world wrong, to commit such evil deeds. This pathological inner rage and narcissistic need for retribution and revenge is at the core of sociopathy--which is why I refer to

Messianic religious sects like Al-Qaeda and ISIS are not unlike the psychedelic cult or "Family" that unquestioningly served and worshipped Charles Manson, obediently butchering the pregnant Sharon Tate and eight others at his bidding in the summer of 1969. Manson was convinced that by instigating a race war in America as a result of the random killings, he and his group would seize power in the ensuing pandemonium of "Helter Skelter." This was his own messianic delusion of being a savior, of saving the world. From what I've seen in taped interviews over the years, Manson appears to be at once narcissistically grandiose, intermittently psychotic, paranoid, and profoundly antisocial. He bitterly alleges--with some merit, given his horrific background before the Hollywood massacre-- that the world has done him wrong, which gives him the right to do the world wrong, to commit such evil deeds. This pathological inner rage and narcissistic need for retribution and revenge is at the core of sociopathy--which is why I refer to  It was an extraordinary story back in May 2012. Strange packages surfaced in several places in Montreal, Canada, that contained body parts. A note attached to a severed foot warned that the killer would strike again. It was mailed to the headquarters of a political party.

It was an extraordinary story back in May 2012. Strange packages surfaced in several places in Montreal, Canada, that contained body parts. A note attached to a severed foot warned that the killer would strike again. It was mailed to the headquarters of a political party. Feeling down, grumpy, agitated, anxious, sad or lonely? There may be a brief, free, and easy technique that you can use right now, without even having

Feeling down, grumpy, agitated, anxious, sad or lonely? There may be a brief, free, and easy technique that you can use right now, without even having

In

In