In my previous post (Part 1 of this essay) I discussed themes related to our feelings of discontent. I described differences between unhappiness, sorrow, and sadness. I considered, with the help of Robert Burton’s 400-year-old masterpiece The Anatomy of Melancholy, some causes of those conditions.

In Part 2 of this essay, I explore feelings of discontent as difficulties in our “relationships” with the world. To be sure, there are different kinds of relationships that affect us. Some discontent is traceable to physiological imbalances. Under such circumstances, medication or other kinds of bodily readjustment and healthful living may be appropriate responses. Pertinent also are persisting psychological disturbances – perhaps traumatic events we have experienced in our lives, addictions we cannot shake, or other destructive behaviors that keep us from operating at our best.

With all respect to those types of causes, and to the psychotherapists and health practitioners that address them, I want to focus here on social and cultural factors as sources of unhappiness.

To be sure, there is a sense in which unhappiness is an individual, even psychological, matter. All of us maintain personal expectations for how the world operates. Some of those anticipations are standards, that is, visions of what we consider preferred or “good” conditions. We don’t like to see our standards violated, especially when the events in question are important to us. At such times, dissatisfaction turns into unhappiness, which may linger within us as sadness and sorrow.

To be unhappy then is to ponder the perceived gap between our understandings of good conditions and the conditions that currently prevail. We feel worse as that gap widens and better as it closes. We feel very good when we exceed those desired conditions (perhaps winning a lottery or getting an unanticipated A on a test). We feel miserable when events descend toward what we conceive to be worst conditions, perhaps realizing our “darkest fears.”

Much of life – and of our quest to be happy ˗ features attempts to reconcile our expectations for existence with the conditions we encounter. Sometimes that means attempting to change those worldly conditions (and by implication our own behaviors) to make them approach those expectations. Alternately, we fiddle with our standards, moderating them so they align better with the lives we lead. Most of us think of maturity or wisdom as the ability to develop reasonable standards, both for ourselves and for the world we live in and, more than that, to decide which things we can change and which things we must endure.

Be clear that the standards we apply are complicated, fluid, and sometimes situation specific. We may have different standards for different areas of life (think of job success, romantic involvement, friendship, family ties, physical well-being, leisure endeavors, and so forth). We may declare some of these areas more important than others (perhaps support of family and friends instead of job success). We may shift the reference groups that are the basis of our standards (perhaps comparing ourselves to “people like us” rather than some vaunted person). We may further adjust that focus by bringing up examples of the terrible things that can happen to people (“Poor Jones is sick; his wife left him; his son is in jail. Really, I should count my blessings.”) We can shift our concern from our own circumstances to those of others, such as our children. Who of us does not rationalize their existence in similar ways?

I once wrote a book that presented the emotions – and happiness, in particular ˗ in those very terms. But this is an incomplete theory of what makes people happy and unhappy.

Although we possess personal standards (sometimes quite rigid ideas) for how the world should operate, other kinds of standards are equally important in our quest to be happy. Those standards include basic physical and psychological needs, the commitments of the groups we belong to, the values of the wider culture, and even our perceptions of the “interests” of ourselves and of others.

What I’m arguing then is these patterns of expectation, essentially expressions of our life conditions, are also crucial elements of happiness. These conditions make claims on us, urging us to do one thing or the other. Some of these claims countermand our cherished values or ideas. In much the same fashion, we also make claims on the life-conditions that confront us. That is to say, our relationships with the world are dialectical affairs, patterns of give-and-take. Frequently, we are able to impose our will on situations, but even more frequently, we have to accede to the wishes of otherness. This interaction is especially apparent in our relationships with other people.

This is the theme ˗ how different kinds of relationships create different kinds of challenges ˗ that I comment on in what follows. I describe four different kinds of relationships: subordination, privilege, marginality, and engagement. Each one generates distinctive possibilities for happiness – and for unhappiness.

Subordination and feelings of Entrapment

Subordination is perhaps the most apparent source of unhappiness, at least in a rights-oriented society like ours. Although there are many occasions where we willingly accept the directives of superiors (think of parents, teachers, coaches, bosses, ministers, and the like), for the most part we like to experience the feeling of being in charge of our own thoughts and behaviors. When we direct our own involvement in the world, we have the best chance of aligning it with our standards. We can start, stop, and otherwise manage our behavior at will. Granted we may fail as often as we succeed. Still, we do this on our own terms.

Under conditions of subordination, others tell us what to do. We may not accept the standards they impose. To make matters worse, there may be little we can do about their ability to control us. Commonly then, we live with a sense of blocked opportunity, of deferred or unrealized dreams. One response is to try to accept the standards others impose on us, and the identities they require us to hold (Karl Marx called this acceptance “false consciousness”). Similarly, we may deny that we have any ability to change our predicament (Jean-Paul Sartre called that denial “bad faith”). Still, we recognize that we are not able to do the same things as other, more advantaged people in our society. I call such feelings of blockage and hopelessness Entrapment.

Privilege and feelings of Normlessness

What if we occupy a position opposite to the one just described? We have resources galore. We can go and do as we please. We are able to control other people instead of being controlled by them. Surely, that condition of privilege is the good life.

Not so. At least that is what the great sociologist Emile Durkheim argued. Durkheim claimed that we humans need social and cultural directives to fulfill ourselves as persons. That is, we need others to express their concern for our welfare; we need to reciprocate that concern. Without that sense of willing obligation to others ˗ call it “responsibility” ˗ we merely bounce around from one self-nominated pursuit to another. Ultimately, we become prisoners of our own desires, which we discover to be endless in their variety and quality of incompletion. At some point, existence follows the tyranny of whim. Durkheim termed that lack of social commitment “anomie,” which is the Greek term for Normlessness.

Once again, our culture – especially our culture of advertising˗ celebrates this ethic of boundless domination. We celebrate freedom of personal choice, however, worthy or unworthy those choices may be. In ads, beautiful people are shown at exotic places pursuing fanciful adventures, all permitted by the passport of money. Smiling others are shown greeting them and doing their bidding. The ideal life, or so it seems, is cultural masturbation.

However, most of know that incessant willfulness is ultimately empty. We need other people around us, not as minions but as persons we care for and respect. Without firm commitments from others, our own standards weaken and collapse. A day at the beach or spa is only that. The better forms of happiness express our caring, consistent involvement in the lives of others.

Marginality and feelings of Isolation

The previous two conditions feature direct relationships with others, though those relationships may not be what we desire or even what is in our best interest. Different from both is the condition where we have few connections to society, perhaps even to family and friends. I call this pattern marginality.

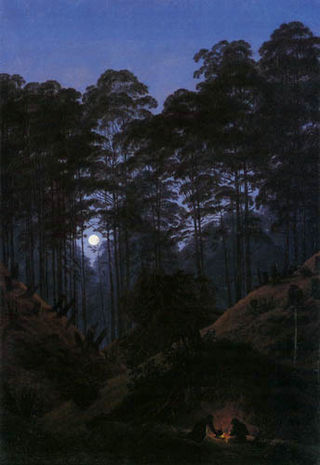

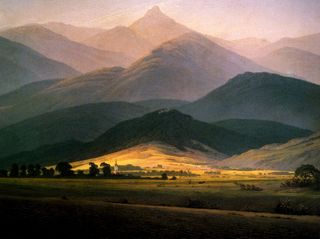

Once again, our society sometimes glamorizes this condition of being on the edge, or perhaps beyond the reach, of society’s powers. Wouldn’t it be grand to be a cowboy alone on the prairie, a solitary mountaineer, or an eccentric genius fascinated with his or her personal creations? Nobody could tell you what to do.

Less glamorously, many people endure this condition as a fact of daily living. They live alone in apartments, wander streets, or stare at the walls of jail cells. Countless others find themselves cut off from society’s normal routes and routines. They are old, poor, physically disabled, psychologically challenged, or marked as outsiders by criteria or gender, religion, nationality, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and other matters.

Perhaps these marginalized people, like the rest of us, find comfort in small circles of family and friends. Perhaps they take pride in their special identities or join organizations that represent their concerns to the public at large. Those limited contacts may be enough to build a satisfying life. But there is inevitably the knowledge that many people in society do not accept them, indeed have marked them with these identities in order to shun them and to restrict their access to that society’s valued resources.

Isolation ˗ the awareness that one is cut off from others, unable to contact them or to receive their contact ˗ is a profound disturbance of its own sort. Defensively, some marginals may insist they don’t want contact with those who reject them. However, all of us need the support of communities of caring support; and our self-estimations expand consistently with the expansion of those communities.

Engagement and feelings of Meaninglessness

Many readers, or so I believe, would say that none of the above types approximates their life-conditions. Those readers are actively involved in their communities of concern. They feel comfortable going about on public byways. They do not expect shunning or reproof. They have little desire to lord it over others; nor do they expect those others to dominate them.

Most relationships with other people feature patterns of give-and-take, and the compromises that result from such dealings. At least that is the case for those who understand themselves to be of the middle-class, of “mainstream” identities, and otherwise unrestricted in their expression of interests and beliefs. Day-to-day interactions for such people feature countless engagements with those of relatively similar status ˗ the store clerk, the plumber, the insurance agent, the coach of the Little league team. Life is an exchange of services, sometimes on money terms.

Rare is the person who would say that their life is not “busy” in just these ways. Even children find themselves over-scheduled. Some enjoy the hectic routine; it makes them feel vibrant and involved. How can any of this be a problem?

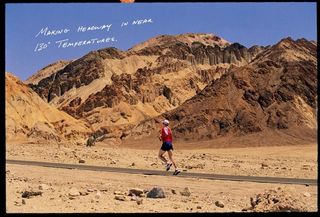

It is a problem, or so I would maintain, if that involvement is mostly a ritualization of life energies. Getting the car serviced, going to the dentist, attending exercise class, meeting with a child’s teacher, turning in a report at work, and so forth may all be necessary enough. However, there should also be occasions where people reaffirm what is fundamentally important in their lives. Potentially, years can go by where the minutiae of existence overwhelm us. Involvement seems like happiness, but is it?

In my view, Meaninglessness is the danger of the over-involved life. For many reasons, we do what we think is required to make our lives, and the lives of our loved ones, successful. But how hard have we thought about the various meanings of “success” or “happiness” and how complicit are we in fabricating a world that entraps the people we care about? Stepping back from routine ˗ and reaffirming fundamental values – is one response to an existence turned robotic.

Being unhappy means that we have somehow departed from our better standards for living. We have lost connection with the basic human resources we need to make our lives whole. Reevaluating those connections, re-imagining our self-trajectories, and redirecting our energies is the challenge of the committed life.

Consider four kinds of relationships and the challenges they pose for happiness.

Being unhappy means we have somehow departed from our better standards for living. We have lost connection with the basic human resources we need to make our lives whole.